It’s one of SA’s most green, pristine spots, famous for its wines, food and that view. Next door, a gold mine wants to open for just five years. In the battle of wineries and mining jobs, who should win?

Cameron England, Business Editor

- Terramin could submit lease application within weeks

- Wineries launch bid to stop gold mine

- Terramin disputes claim of risk to Hills economy

It’s winter in the Adelaide Hills, and a more bucolic, picture-postcard wine and food region you’d be hard pressed to find worldwide.

A scant number of workers are meandering through the grape vines, now dormant after a harvest destined to be turned into Australia’s best rieslings and sparkling whites, wine tourists cosy up to wood fires in cellar doors such as Bird in Hand, Artwine and Petaluma, and roadside stalls sell apples by the bag and punnets of freshly picked berries.

But in the midst of this advertisement for clean-green produce, sits — to some — a sleeping threat.

This threat is an underground gold mine, owned by Adelaide company Terramin, which the company wants to restart and run for five years or longer.

Many locals, who have been fighting the mining project for years, say there’s just no way that mining and agriculture — wine, beef, apples, strawberries — can coexist with mining.

And why would you risk another hundred years of produce and tourism for a five-year economic sugar hit, they ask?

Terramin say they’ve gone out of their way to reduce the impacts of the planned mine, and that they can do it without harming either the water table, or affecting surrounding businesses.

The company says its approach to the project — including planting 40,000 native trees to almost entirely remove the visual impact — shows that it’s a company that “listens and responds”.

Chief executive Richard Taylor said there were many in the community that supported the project as a source of jobs and economic input, and he was disappointed by the “scare campaign’’ its opponents with intractable views were running.

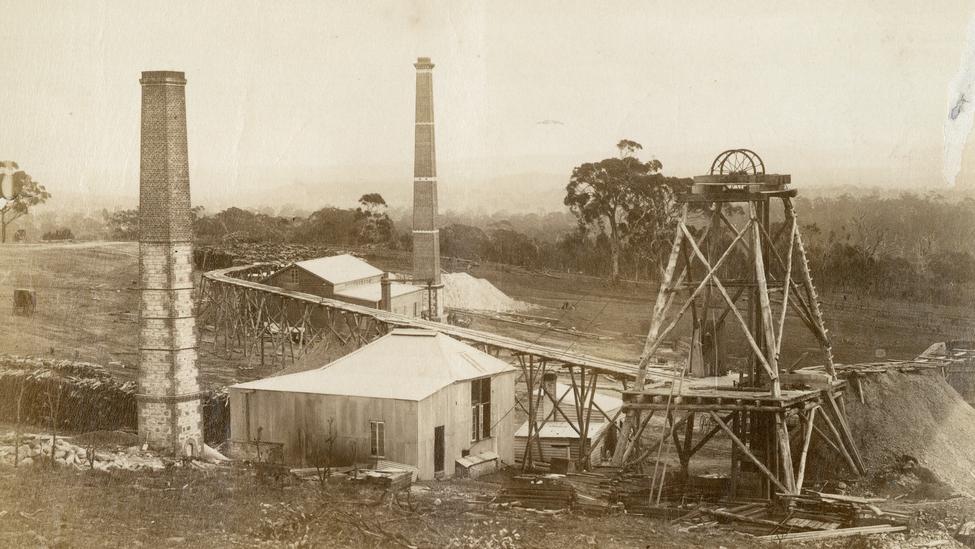

He points out mining has underpinned the economy of the Adelaide Hills since the late 1800s, with Terramin’s own zinc mine at Strathalbyn operating for five years to 2013 and Hillgrove Resources’ Kanmantoo copper mine operating safely in recent years also.

This particular fight at Bird in Hand has been going on for more than a decade. It will come to a head soon, with Terramin saying recently it expects to lodge its mining lease application with the State Government “within weeks”.

The agriculturalists

Nikki Roberts moved to the Woodside area to live because she wanted a rural, village life, and to be closer to her employment at Bird in Hand winery, where she is a marketing executive.

She’s invested in the community and the local economy, both literally and figuratively, and is adamant that mining is no longer appropriate in the area.

Ms Roberts’ views are shared by many — but not all — of the businesses that neighbour the mine, which sits adjacent to three wineries and not far from other primary producers such as the AF Parker & Sons apple and strawberry farm.

When The Advertiser visited this week, there were representatives from Bird in Hand, Artwine, Petaluma, AF Parker & Sons, Accolade Wines, the Adelaide Hills Wine Region, and Jim Franklin-McEvoy, a local grazier who also heads up the Inverbrackie Creek Catchment Group.

“You asked if you thought the two could work together,’’ Ms Roberts says.

“The answer is, quite simply, no. This is where we live, it’s where we make our livelihood. it’s not only about the groundwater that is so important to supply our agriculture, it’s also the perception of the region.

“Tourism is a massive element for the Hills. eventing at our place or many of the Hills venues wouldn’t be nearly as attractive with trucks running up and down the road.

“I moved to the Hills because it’s a beautiful, clean, green, healthy, safe environment for my kids.’’

Jared Stringer, vice president of the Adelaide Hills Wine region, said farmers were stewards of the land, and treated water supplies with respect.

He wasn’t convinced that a mining company with a five-year horizon would have the same priorities.

Mr Stringer said the project was only meant to be approved if it would create “no harm” to surrounding businesses and the environment, and that was impossible to guarantee.

“We don’t know how many customers would be turned away by the dust, and the noise and the heavy traffic on the roads, there are no guarantees we wouldn’t be harmed if this went ahead.”

“They have no guarantees about anything,’’ Mr Parker said.

Mr McEvoy said the area had already changed dramatically in terms of what was grown, with a movement away from water-hungry potatoes and dairy to other crops, as a result of a reduction in water supply over the years.

Mike Mudge, winemaker and site manager at Petaluma, said there were fears about the future plans of Terramin and other companies, with Terramin already stating its intent to grow mining in the region.

“This potentially is the tip of the iceberg,’’ he said. “Our former premier opened our winery, based on the credentials of it being a green environment, which is totally contrary to what’s planned.’’

Mr McEvoy said the “quality and the quantity of the water” was the foremost concern of the agriculture sector.

While Terramin had a scientific model that predicted minimal impact, Mr McEvoy said it was an inexact science and “it’s that uncertainty which is a problem’’.

Mr McEvoy said the project included 24 truck movements a day, trucking ore to the processing plant at Strathalbyn, and there would be dust, noise and visual impacts.

the mining company

For its part, Terramin says it can operate in an environmentally-friendly manner, and Mr Taylor points out that mining is held to a much higher standard than other industries, including the wine sector.

The company has already planted 40,000 native plants at the site to hide most of the operations from view, and has produced water monitoring reports showing through a combination of sealing the mine and reinjecting water, it won’t impact the groundwater.

Terramin has estimated the mine would employ 140 people directly, generating $6.4 million in salaries per year.

About $34 million would be invested to build the mine with another $30 million per year spent on operating expenditure.

Mr Taylor said Terramin had safely operated the Angas zinc mine at Strathalbyn from 2008 to 2013, and had shown there that it was a good corporate citizen.

He said feedback from community consultation naturally brought up concerns around water and other impacts, but that there was strong support from businesses and those seeking employment.

“We’re complying with some of the strictest conditions that have ever been put (on a project such as this) to the point where we will have minimal impact on the neighbours and the area, and we’ll bring positives in terms of jobs and economic growth,’’ Mr Taylor said.

Mr Taylor said there would be no processing on site, with the above-ground infrastructure similar to other sheds in the area used for wine production.

“We’ve really made big efforts to redesign the project such that we have a small footprint. We have a buffer zone around us, we’ve planted 40,000 trees, engaged landscape architects to ensure that our neighbours have minimal visuals of the project. There’s no processing, there’s no chemicals.’’

The State Government, and Energy and Mining Minister Dan van Holst Pellekaan, are waiting to see what Terramin submits before making a judgment.

The process will need to be signed off by both Mr Pellekaan and Environment and Water Minister David Speirs if it is to go ahead.

With the Government already split on land access for minerals exploration — with Hills MP Dan Cregan among Liberal MPs who crossed the floor — it’s sure to be a debate that will play out for some time.